Rubens, Venus and Adonis, 1630s

Rubens, Venus and Adonis, 1630s

“Sometimes the hardest thing to give up is actually the thing most likely to make us better.” The icebreaker question drew out a number of “things of the world” we thought were both impossible to give up and critical to our very happiness. Often these fell into the generic “wine, women, and song,” either the real deal in our youth or echoes thereof since. As we reflected personally on some of these, an interesting pattern developed. Rather than creating pain, the give-up created joy. Giving up excessive drinking after work led not to stress and more headaches but rather to greater clarity of mind and focus on work and our families. Giving up our worst, most embarrassing sins in a deep confession led not to humiliation and sadness but rather relief and gratitude for God’s mercy. Giving up a social media addiction led not to loneliness but to liberation and stronger relationships. Even giving up a special spiritual “souvenir” that seemed irreplaceable led not to loss but abundance. As we thought it through, there could only be one real conclusion: giving up something of the world for a greater good almost always makes us better, happier, and stronger. What habit or thing am I currently hanging onto as “irreplaceable” that God is nagging me, deep inside, to give up? Is there any better time than now to do just that?

Donatello, Magdalen Penitent, 1450s

“The Dead Sea is dead because it only receives. It never gives.” One of the keys to spiritual growth is giving of ourselves out of our poverty. If we’re not giving, we are only on the receiving end of things, and when that’s all we have, we’re dead. As we reflected on big things we’d given up, some of us brought up constructive actions that we did in lieu of what we’d given up. Universally, this list made us better, especially when it involved doing something sacrificial for the other and/or for God. It is only in giving out of our poverty, whether that be money or time, that we truly give. And when we do give out of our poverty, all of the examples we had resulted in us getting more back in love, or growth, or fulfillment, or even in “Pope rosaries” than we’d first given up so cautiously. The Lord is like that. Peter agrees reluctantly to “put out into deep water” (Lk 5:4), and next thing he knows, Jesus dumps so many fish on him that it nearly sinks his boat! Are we thinking positively enough about Lent? Are we thinking about what we can give that would really hurt?

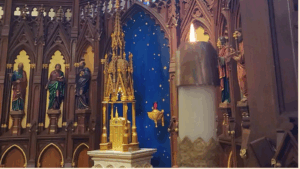

“The devil is a gentleman.” As we walked through the gospel reading, we concluded that the devil is really a pretty wily creature. On the surface, he’s a gentleman. He seems to be on our side, giving us all the rationales we need to waltz directly into the trap of sin and death. How many times have we heard him whisper to us, “That’s not really a sin. What’s the big deal?”, or “You deserve this. You’ve had a long day.” Appealing to our great capacity for self-pity, self-delusion, and self-aggrandizement, he can draw us into a seemingly innocent dialogue that is the first step down a slippery slope where things only worsen. In dealing with the devil in the gospel passage, Jesus wins partly by not engaging. Every time Satan proffers an excuse or temptation, he quickly shuts it down and brings his focus back on his Father. Like Adonis in Rubens’ masterpiece “Venus and Adonis,” Jesus never looks the devil in the eye. Rather, he plants his spear forward toward his mission, toward God, and never looks back. Are we staying clear of the occasions of sin in our lives? Are we avoiding at all costs engaging in a dialogue with the devil? If we aren’t, maybe this Lent would be a good time to start.

“Penance, Lent, requires deep remorse for what we’ve done.” The Art Corner allowed us to reflect on the two sides of penance. Donatello’s late masterpiece, “The Magdalen Penitent,” could be, as art historians often guess, an image of St. Mary of the Desert, one of the first ascetic saints of early Christendom. And maybe it’s what we’re supposed to look like physically after a grueling Lenten fast. But that’s not what we saw or what Psalm 6 that we reflected on hinted at or why Donatello referred to his masterpiece as “Magdalen.” What we saw, was a soul truly penitent, mortified by the sin she’d committed and pleading with God for forgiveness.” “Do not reprove me in your anger, Lord, nor punish me in your wrath… Heal me, Lord, for my bones are shuddering.” (Ps 6:2-3). Are we approaching the penance of Lent with a truly penitential heart? Or are we just going through the motions because “that’s what we do in Lent.”

Georges de la Tour, The Penitent Magdalen, 1640

Georges de la Tour, The Penitent Magdalen, 1640

“Let Lent be the beginning of a transformative journey towards Christ.” The other side of penance is its ability to transform us closer to the perfect souls that the Lord created us to be, wants us to be, and will help us to be. We saw this side in La Tour’s take on Magdalen. Here, following her deep contrition and conversion, she sits calmly, no longer afraid of death though perhaps concerned that the temptations of yesterday will still be ahead, calling her off course. She gasps with a kind of peaceful happiness when Jesus appears to her, reminding her that he will be accompanying her on her journey. “Mary,” he whispers. Then she sees Him with her. “You discern my going out and my lying down.. you are familiar with all my ways… You hem me in from behind and before.” (Ps 139:1-7) Do we embrace enough the journey forward with Christ? Do we need an attitude adjustment on the topic of Lent? Do we need to see Lent more as a chance for a beautiful transformation than a painful series of sacrifices?

Resolution: As we contemplate our Lenten prayer, almsgiving, and sacrifice, we will each pray for inspiration to give up something in our lives that, in one form or another, is keeping us from drawing closer to God. We agreed to “push the envelope” on this self-ask. Secondly, we resolved each night in Lent to do a full conscience examination.

Insights from a men’s leadership circle discussion.