It all began at 10 years old when my 15-cent weekly allowance was eliminated.

My dad pulled me aside and said, “Michael, now that you are caddying and earning your own money, your household chores are simply what it means to be part of the family and part of the team.”

It started with setting the table, dusting and vacuuming the living room and family room, and occasionally folding the clothes.

Then it gradually progressed to taking over my two older brothers’ jobs of helping with the dishes, pots and pans, taking out the garbage, washing the car, and most importantly, cutting the grass in summer and shoveling the driveway in winters.

Looking back, it was not a big deal; it was simply what was expected of me and most of my friends at home. My mom was a full time second grade school teacher, and aside from doing the laundry (which included a lot of grass stains and ripped pants from our football games), she was always cooking, painting, and putting together flower arrangements for the sick and dying in our community — AND taking care of my wheelchair-bound older sister.

My dad woke up at 4 a.m. to drive into downtown Detroit for a long day at Ford Motor Company, and at times, he traveled extensively … so this was the least we could do.

While many of the kids in my hometown of Bloomfield Hills, Michigan, were hitting golf balls and enjoying themselves at their country club, my two older brothers and I spent our summers caddying (at times for our neighbors) and working as busboys and in the locker room as well. Although our parents paid for a top class Catholic grade school and high school education (St. Hugo’s and Brother Rice High School), and most of our college tuition, they made a clear distinction between “needs” and “wants.”

They covered our needs; we paid for our wants. So my cool pair of sunglasses, my Bermuda shorts and Izod shirts, new golf clubs, going to the movies and concerts, etc. — all of this came directly from my caddying funds.

Table manners, bedtimes and curfews (with a breath test and a few questions at the door) were also strictly enforced, as well a zero tolerance policy for bad language in the home or any type of disrespect, especially toward my mom. My dad definitely had my mom’s back and they were on the same page, all the time, when it came to enforcing infractions. It was always fair, and it came from a place of love.

My dad feared that growing up surrounded by privilege, we kids would morph into entitled, spoiled brats. One summer day, he asked to inspect my effort in washing his car. I had rushed through the job because my buddies were playing basketball across the street and were begging me to join them. Naturally, that’s all I wanted to do.

After pointing out dust on the dashboard, dirty hubcaps and missed spots on the bumper, my dad said, “I know you want to play basketball and I know you think I’m being a little too tough. But I want to develop in you a habit of solid discipline and a habit of doing everything with excellence. I could say nothing and allow you to be just an average kid … or I could point out these details and inspire you, I hope, to reach your potential in absolutely everything that you do. Get the point?”

I got the point.

There are two types of pain — the pain of discipline and the pain of regret. Thanks, Mom and Dad, for choosing discipline.

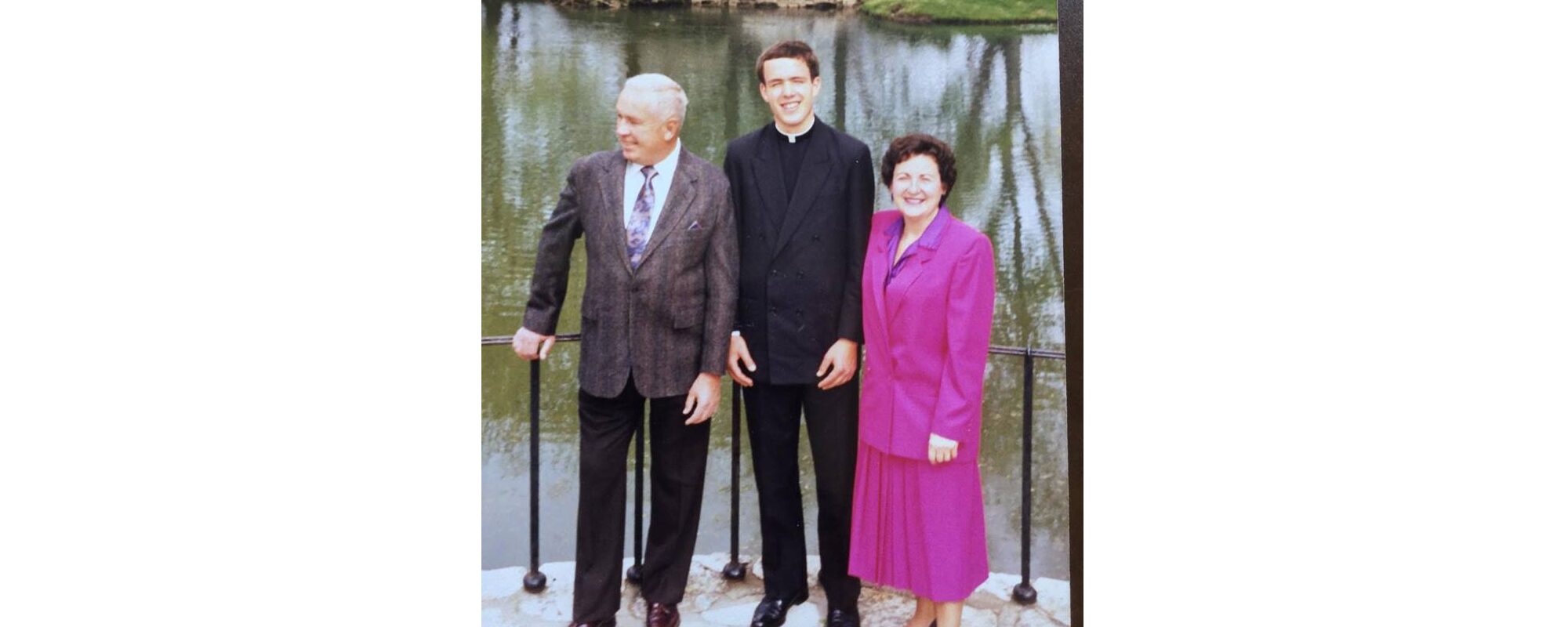

Fr. Michael Sliney, LC, is a Catholic priest who is the New York chaplain of the Lumen Institute, an association of business and cultural leaders.